Lee Camp

[00:00:00] I'm Lee C. Camp and this is No Small Endeavor - exploring what it means to live a good life.

Charlie Strobel

Forgiveness creates a peaceful, peaceful heart.

Lee Camp

That's Charles Strobel. Charlie, as most everyone called him, was a Catholic priest and founder of Room In The Inn, a Nashville-based nonprofit that gives hospitality, education, and work to those experiencing homelessness.

Charlie died August 6th, 2023. Today we're re-airing an interview taped in 2020. Even if you were lucky enough to know him very well, you may hear some things you did not know from this beautiful man who offered shelter and friendship to so many.

Charlie Strobel

The beauty of what you are doing for me in this conversation is that you're allowing me to say some things that I haven't said.

Lee Camp

Coming right up.[00:01:00]

I'm Lee C. Camp. This is No Small Endeavor - exploring what it means to live a good life.

Charles Strobel, Catholic priest, was a founder of Room In The Inn, a Nashville-based nonprofit that gives hospitality, education, community, and work to those experiencing homelessness. He was also something like a patron saint of Nashville, given accolades like 'Tennessean of the Year' numerous times.

Surely he was imperfect, but beloved. Charlie, as most folks around town seemed to call him, died August 6th, 2023, at the age of 80.

I had the privilege of counting Charlie a friend. He was a friend who always treated me much better than I deserved, and inevitably, I left every encounter with Charlie encouraged, feeling as if I had been seen, cared for, and cared about.[00:02:00]

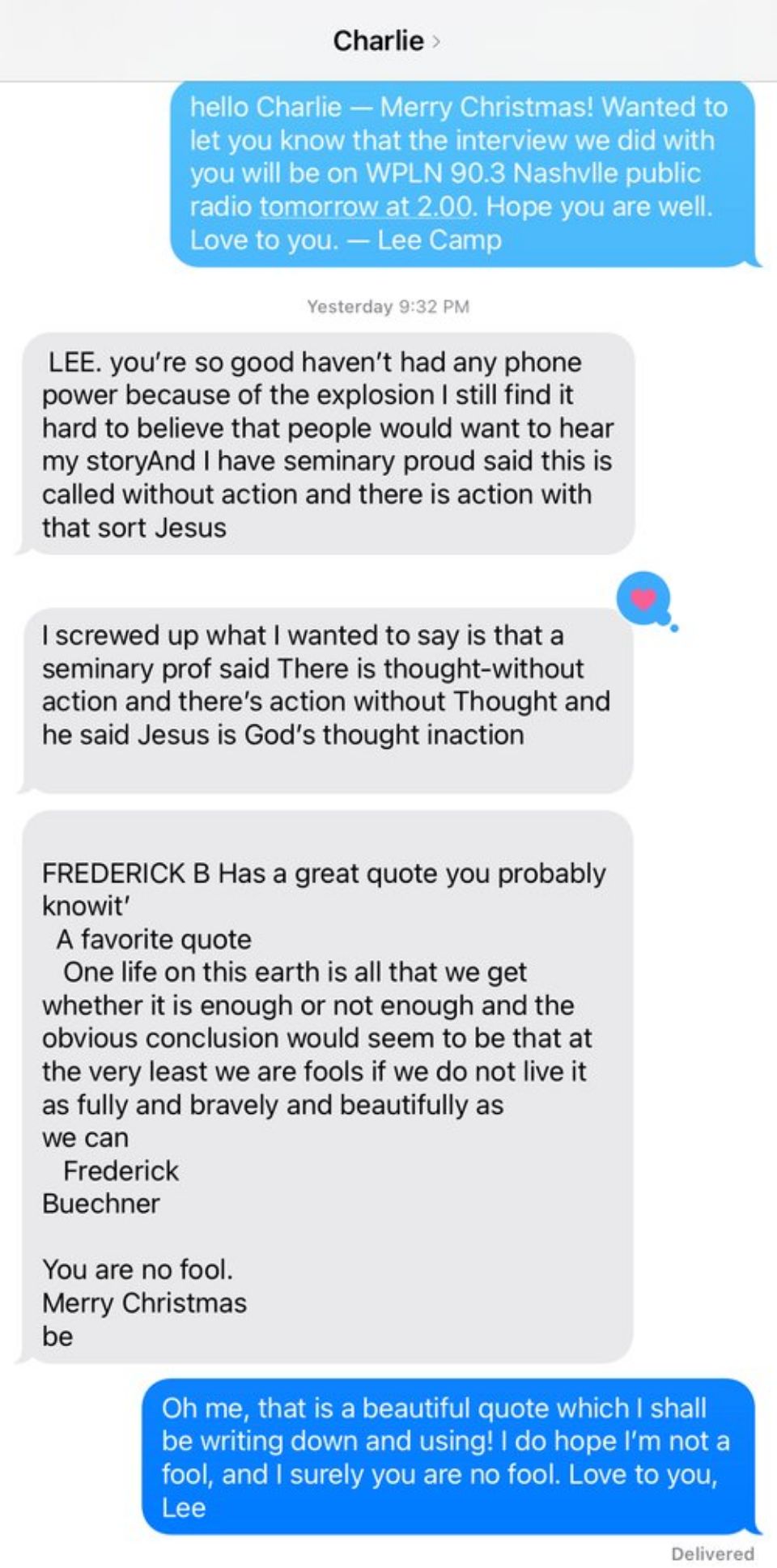

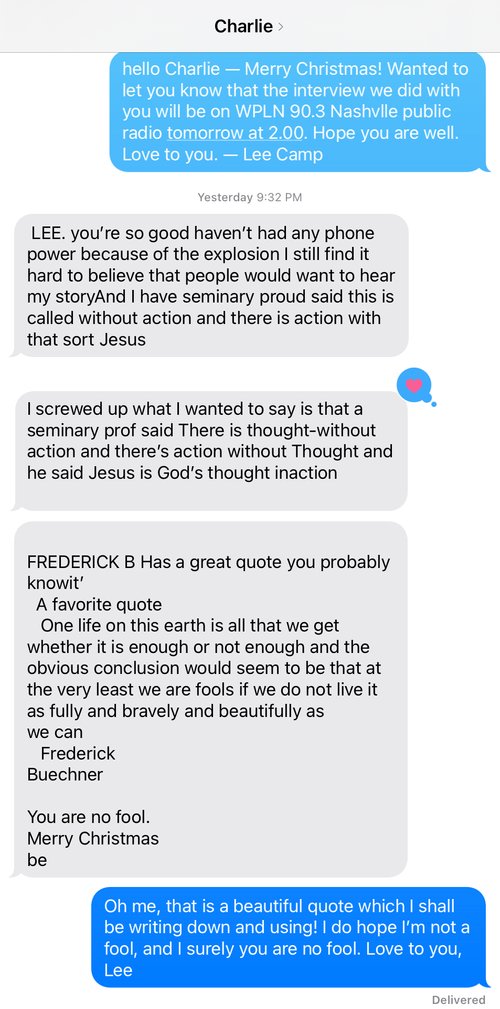

I keep on the desktop of my computer a folder, simply labeled "gifts." There are pictures of friends, scans of some correspondence, reminders of graces. In that folder is a screenshot of a text exchange I had with Charlie. That exchange occurred not too long after we taped the interview you'll hear today, which was taped in August of 2020.

Charlie's message said this, "Frederick Buechner has a great quote. You probably know it. 'One life on this earth is all that we get, whether it is enough or not enough, and the obvious conclusion would seem to be that at the very least we are fools if we do not live it as fully and bravely and beautifully as we can.'"

Then Charlie's message closed to me saying, "You are no fool. Merry Christmas."

Whether I'm a fool, I do not know. But I feel quite certain Charlie was not, [00:03:00] and we grieve his passing.

Charlie came to our house early in the pandemic. We sat down in my study, socially distanced, to take the interview, and Charlie, ever the pastoral presence, started that interview by asking me how I was doing.

Charlie Strobel

Lee Camp

I have been, on the whole, good. I've chosen to work really hard since March, and so I've, I've been really busy. And when I would start to feel lonely or isolated, I'd just work some more to--

Charlie Strobel

Lee Camp

--work through my feeling isolated.

Charlie Strobel

Well, you, that's what I do.

Lee Camp

Charlie Strobel

Yeah.

And you know, you say it, lonely and isolated.

I wish I could remember to quote it, but the difference between solitude and loneliness, there is a difference.

Lee Camp

Charlie Strobel

And solitude is, trends toward God. Loneliness tends toward self. Being lonely is the plight of all of us at some point. The solitude of loneliness is the steps before you encounter the burning bush.

Lee Camp

Charlie Strobel

And I mean, it's not easy to to say that that happens. And in fact, most of the time it, it doesn't happen. But being lonely can lead us to God.

Lee Camp

I went through a period of feeling lots of loneliness in my, kind of in mid lifetime, accompanied with a lot of depression for a while.

Charlie Strobel

Lee Camp

And I think one thing that helped me was just a sort of acceptance that, like you [00:05:00] said, that loneliness seems to be the plight of all of us at some point in some way.

Charlie Strobel

Lee Camp

And, because I started thinking, you know, no one can fully know me.

Charlie Strobel

Lee Camp

Because no one has the time to sit and listen to even one day's full experience, right?

Charlie Strobel

Lee Camp

And so there's always elements of me, even with those that I'm closest to, that they're still not necessarily gonna know.

Charlie Strobel

Lee Camp

And so, I think once I came to that place of thinking, well, that's just the nature of what it means to be human, is that there's a certain reality of loneliness in that regard--

Charlie Strobel

Lee Camp

--that happens all the time, and then trying to find practices like you, like we already said, to let go of the self-centeredness that I would have in my loneliness and tend towards trying to cultivate solitude instead.

Charlie Strobel

Yeah. Being wrapped [00:06:00] up in oneself to the point where we work ourselves into a frenzy and to justify that we are good and all, being wrapped up in that amount of energy, and they call it workaholic and all, is a great distraction from something that we might be afraid to face.

I've been in therapy and, um, wanted to get behind the curtain. And I began to realize that I was my own therapist.

Lee Camp

Charlie Strobel

I started asking and talking about the problems I was having, and the, the counselor just sat there and I said, "This is the easiest money you've ever made."

[Lee [00:07:00] laughs]

I said, "I'm doing all the talking and the asking." And he said, "You're right." But he was there to, to give me feedback when I asked for it.

But I, when I said going behind the curtain, I realized somewhere in that, in that experience-- and it, I went to therapy for eight years or so. Um...

Lee Camp

And you, how old were you at that point?

Charlie Strobel

Well, it was after my mother died. I was 40-- maybe 45 or so. And, um, I would come in, sit down and start talking, and in 50 minutes I'd get up and leave, come back the same way, and I kept doing it and doing it.

And each time I kind of addressed some issue in my life, either as a young boy or as a seminarian, [00:08:00] as a priest, as somebody trying to do something with the homeless, as a sibling, and I kept atta-- attacking these issues and not, not coming to conclusions as much as it was just a matter of, 'golly, I got that outta me.'

Lee Camp

Charlie Strobel

'And I got that outta me.' And I began to feel light inside. Not l-i-g-h-t. That too, there was enlightenment for sure. But I, I was not as heavy and-- emotionally, as I was when I started.

And, um, not too many people know-- I don't know how much of this is going over the air. Not too many people know what I've been saying, and you tricked me!

[Both laugh]

No, no. I-- the, the beauty of what you [00:09:00] are doing for me in this conversation is that you're allowing me to say some things that I haven't said and, um... you can give me your bill at the end.

Lee: [Laughs]

I, I do wonder, I do wonder-- so I think... for those who, let me just use the language of 'helping professions,' and I think that could be priests, pastors, counselors, teachers, social workers... I don't know, it seems to me that very often there is a deep loneliness that folks in those professions carry about.

Charlie Strobel

Lee Camp

And I would think that it-- some people would be surprised that a priest at 45 is going to therapy. But I've had my times of going to years of therapy, you know, and it's like that same sort [00:10:00] of experience of these things that feel so deeply heavy in me, and when I'm able to process them in a space of vulnerability and trust, that it allows the shame or the pain or the weight of those things to be lightened...

Charlie Strobel

Lee Camp

...in this beautiful sort of way.

Charlie Strobel

Lee Camp

Charlie Strobel

I found that my therapist helped me to know that I also contributed to the answers.

Lee Camp

Charlie Strobel

And that he helped me to, to uh, e-- expose all of the problems, all of the, um, beauty, which I didn't appreciate.

Lee Camp

Charlie Strobel

Well, oftentimes, uh, we fail to see the goodness in our own lives, [00:11:00] and we need someone to tell us.

Lee Camp

Charlie Strobel

And I think in, in so many ways when what-- somebody goes into therapy or treatment, they're looking to be told and to reminded that they are good.

Lee Camp

When you think back about things you've carried with you and you look back, say, to your childhood experience, what are things that you look back as a young boy in Germantown, right?

Charlie Strobel

Lee Camp

That are those elements of beauty that you remember at this point in your life, and what are elements of challenge or struggles that you had to process as a boy that you've, that you've also carried with you, that have given you certain characteristics about--

Charlie Strobel

Lee Camp

--the way you've made your way through life?

Charlie Strobel

Well, the first, uh, thought I had, as you were asking the question, was my daddy. I wish I had brought a [00:12:00] poem that he wrote about, uh, his wife, my mother. But he was, uh, handicapped as a two-year-old. He fell, he was at the top of a makeshift seesaw, and the little kid at the bottom got off the, the, the board and he landed on some concrete.

Lee Camp

Charlie Strobel

So he was two years old. And, um, without anybody knowing what to do, they, they hung him in suspension in the doorway to-- for years, hoping that the, um, weight of his body would straighten out his spine.

Lee Camp

Charlie Strobel

But he, it didn't, and he was unable to walk until, until he was eight. And, um, he had a broken back and, uh, he became a hunchback.

Lee Camp

Charlie Strobel

His nickname was Mutt. He wasn't able to work a steady [00:13:00] job as he grew older, but eventually became an employee of the fire department and was a dispatcher and everybody in the fire department loved him. And so when he died, suddenly, at 47, they went to the fire chief and said, 'would you give his wife the job of clerk?'

And so that was in '48, and sure enough, the chief gave her her the job. She became the first female in the Nashville Fire Department.

But I've always wanted to know him better. And some of the sadness I carry is the sadness for not knowing the father. I think there's not so much sadness about wanting to know him, but more a yearning.

I think he, he sort of becomes [00:14:00] a parable, uh, that reminds me of God the Father.

Lee Camp

Charlie Strobel

So, um, that's both the, the positive, uh, aspect of being his son and the yearning to see him--

Lee Camp

Charlie Strobel

--and to know him even better.

I used to pretend to cut his hair and put a sheet around him and go around his head and cut his hair while he read the morning paper.

[Lee laughs]

Well, he, he was smart enough to know he wanted to read the paper and this little boy, he's keeping me from it. Why don't we be play barbershop and I get to read the paper and you get to cut my hair? And it worked.

But I also remember him coming home on a night, night shift at 11 [00:15:00] o'clock at night or coming in to the-- and getting up to go to work at the 7 o'clock shift. And, uh, in their house there's the black skillet with bacon and eggs and, and, uh, biscuits and all, the smell of all of that as a little boy. Jumping up and going to jump in his lap.

I also went with him, uh, when his, um, the pastor at the church had to go make a sick, they call it sick call, going to the hospital or to the nursing home. And, uh, the pastor could not drive. And so my dad drove him to all these different places. And I was in, in the backseat, bouncing around, and just feeling really close.

And so, um, I think that's a, a relationship that is still incomplete. And so there's both the positive part of, [00:16:00] of it being the expression and the parable of, of God as Father. And then there's the negative side of it.

Lee Camp

Hmm.

Thank you for sharing that. That's-- those are beautiful stories.

Charlie Strobel

Well, you describe the stories as beautiful and that to me is a gift that you, what you sense is beauty, and, uh, love.

And that's a good reminder to me of what I've experienced in life.

Lee Camp

You're listening to No Small Endeavor and our conversation with Charlie Strobel, a patron saint of Nashville, and founder of Room In the Inn. Charlie passed away on August [00:17:00] 6th, 2023, at the age of 80.

I love hearing from you. Tell us what you're reading, who you're paying attention to, or send us feedback about today's episode. You can reach me at lee@nosmallendeavor.com.

You can get show notes for this episode in your podcast app or wherever you listen. These notes include links to resources mentioned in the episode, as well as a full transcript. Be sure to follow No Small Endeavor so you don't miss a single episode.

We'd be delighted if you tell your friends about No Small Endeavor and invite them to join us on the podcast. Please go give us one of those nice five star reviews on your favorite podcast app.

Coming up, Charlie tells about his experience among friends experiencing homelessness in Nashville, and how he came to forgive the man who murdered his mother.

[00:18:00] So four siblings, there in Germantown, and I remember you telling me stories about going down to, I think what you called it was 'the jungle.'

Charlie Strobel

Oh yeah. Now picture me, I'm 12 years old and my best friend is Jack Link. He's also 12. And so we're-- run the neighborhood. And we came to see a group of, right now they would be called street alcoholics, but at the time they were called bums and winos, and they all gathered in a clump of bushes and weeds called 'the jungle.'

And it was right where the Bicentennial Mall sits. At first, the two of us decided we would hassle them by, uh, getting our bikes and taking some firecrackers or cherry bombs and drive through there and-- when [00:19:00] they're asleep in the early evening, and throw the firecrackers into the fire. And of course that blew up everything.

And we did that pretending we were American fighters bombing cities in the war.

Lee Camp

Charlie Strobel

Well, they, it stirred them and they couldn't do anything. They were so intoxicated, they couldn't chase us and or holler at us. They, they really kind of just took it. And, um, even at 12 you can develop a conscience. And I just remember the two of us looking at it after we had done this several times, looking at, um, each other and saying, this isn't fun anymore.

So we stopped doing it. Now the next thing then, is to get, try to get in-- inside the camp and become part of the camp. So we weaseled our way in and they took [00:20:00] us in and, uh, we sat around the campfire and they told us stories. And they treated us just like we were a little brother or a son.

Lee Camp

Charlie Strobel

And, um, kind of adopted us. And, uh, we became part of the club, as we called it.

And, uh, that bonded us to them, uh, to the point where I never have forgotten. And whenever I was starting to do some of the, uh, outreach to the homeless, once I got ordained and was at Holy Name, we started the guest house with the police department, which became and is an alternative to public intoxication arrest for the-- at the jail.

So, um, the judges approached me about doing something to, to reduce the jail population, since being [00:21:00] publicly intoxicated was a misdemeanor and it was just clogging up the court. So we started the guest house and it's, it's operational for the police to bring people in and let-- rather than arresting them, and treating them as a social, medical problem rather than a, a criminal problem.

And looking back, I can see that my bringing them in is kind of the extension of their bringing us into their campfire. So I feel like I'm re-- repaying them for the kindness they showed to me. Because they did, they tried to teach us how to live, how to be kind.

Clayton was the ring leader of the, of 'the band of brothers,' I called 'em.

Lee Camp

Charlie Strobel

And his only crime was to be intoxicated. And there was one [00:22:00] police officer who was extremely mean. And we all said that he was the one we need to stay away from because he would arrest us or or hassle us and scare us.

And back then they had what they call a paddy wagon and he, I remember him picking on Clayton. And he was drunk on the sidewalk and so he picked him up and threw him in the back of this paddy wagon, and it was all metal inside, and I can remember his head hitting the metal and, uh, kind of knocking him out.

Lee Camp

Charlie Strobel

And, um, I was, wasn't able to do anything to help him except I, I said to the police officer, um, "He didn't do anything."

And he said, "You want me to throw you in there too?" And I ran away. And I thought, uh, that, that didn't do much to help him. [00:23:00]

Lee Camp

And you were, you were still how old at that point?

Charlie Strobel

Oh, probably 12 to the 14. I was born in 1943. So by the time you get to 1950, there, there's the whole problem with integration.

Lee Camp

Charlie Strobel

And our neighborhood was a mixed neighborhood, which we were, we were happy.... We had a house and we basically, we, it was a-- the neighborhood where the poor helped the poor, and worked for the poor, worked for each other.

There were horse-drawn wagons. That's-- that men drove around the neighborhood. Horse-drawn. Nobody can imagine that, but that's, that's the reality of that-- 1950 to 1960.

They sold coal on the-- for the coal furnace and grates that they, um, everybody had, the lumps of coal. They sold ice for an ice box. No, um, [00:24:00] refrigerators. Ice boxes.

And then there was a fellow who came down to the alley and it was his horse-drawn wagon and he had a couple of 55 barrel drums that was, that was full of food garbage, and fed it to his hogs.

Lee Camp

Charlie Strobel

He was called 'the slop pan.'

Lee Camp

Charlie Strobel

We would, um, just take the garbage to him and he'd, he'd poured in this 55 barrel drum, which was soupy looking, you can imagine.

[Lee laughs]

And, and half, half the flies in Nashville would've been there.

But, uh, it was, um, it was a different world and, and it, um, was full of the same things that we're fighting with now. War, prejudice, hatred, and all the kinds of, uh, of [00:25:00] social justice issues. It was, they were there. I really couldn't articulate 'em, but I knew that there was, there was something wrong whenever you saw a white water fountain and a colored water fountain. You, you didn't know why, but you made some critical judgements about it.

I remember the Knickerbocker Theater was at Capital Boulevard and Church Street, but they had a balcony called a white balcony and a colored balcony, and I can remember thinking, why is there a colored balcony? Wonder what it looks like.

So I slipped up past a usher. I went to the white balcony and knew what that was like. And then I ran up and slipped up through the colored balcony, and it looked just like the white balcony. Well in, in a simple way, a [00:26:00] boy can make judgments. They're smart enough--

Lee Camp

Charlie Strobel

--to develop conscience. And that's why this movement that is throughout our land is such a powerful expression of, of justice, because young people, who've been told whatever they've been told about what is the real world and what the real world is like, they have enough sense to say, "I don't believe in that real world."

And, um, I think that's our hope for our future, that we've got a generation that has seen enough that they're going to put their mask on and they're gonna walk to the capitol or to the courthouse and claim the right to do that without punishment or without jail time.

They're willing to do it, just as we were [00:27:00] willing to do it in the '60s when I was in school at Catholic University in, um, Washington, D.C. I was up there from '65 to '70.

Lee Camp

Oh, was that, uh, seminary years?

Charlie Strobel

Yeah, my seminary years.

And, um, those-- if you could, if, if you would ask me, what five years would you like to be in Washington, D.C. In the last hundred years, I would've, I would say from 1965 to 1970.

And I was lucky enough to be a part of that experience and, um, all of-- the Resurrection City, the Poor People's Campaign, the March on Washington, all of those experiences we were a part of.

Lee Camp

Charlie Strobel

And in saying that, I'm not saying we were pure. Our motivation wasn't a hundred percent committed to social justice and the reform of of [00:28:00] America. We also wanted to meet some girls.

[Lee laughs]

And when you, you could sign up to become a, um, marshal, to say you're a marshal, and you were looking out for the protestors, making sure they were okay, especially the pretty ones.

Lee Camp

Charlie Strobel

But I'd say 80% of us were committed to social justice. The other 20%, we'd fail.

Lee Camp

I have, I have a good friend who once told me that, that, uh... that he didn't believe that anyone ever had completely pure motives in anything. And I've kind of accepted that as, as a sort of good acceptance, you know?

Charlie Strobel

Lee Camp

We don't fall quite so prey to, uh, delusions of our self-righteousness if we accept that, I think.

Charlie Strobel

Yeah. Uh, yeah. Being honest, you know, you did it for a lot of different [00:29:00]reasons.

Lee Camp

Charlie Strobel

Yeah. Uh, but, uh, the point is that you did it.

Lee Camp

Charlie Strobel

Lee Camp

Charlie Strobel

Lee Camp

I wanna go back to something you said early on, kind of where we started. You wish that we could hear a poem your father had written for your mother. Do, do you remember any lines there or what, what he said about your mother?

Charlie Strobel

Oh, I do. He, he starts by saying something like, 'I have no Mayflower ancestry, but still I'm made of sturdy stuff, and I love you. Is that enough?'

Lee Camp

Charlie Strobel

And it was enough. He was crippled. And my mother took about seven or eight years to decide to marry him.

Lee Camp

Charlie Strobel

And I said, "Mom, why did you wait so long?" She said, "I wished I had not have-- had a dozen, I'd loved to have a dozen children."

And I said, I said, [00:30:00] "Well, what, what would you keep you from doing it? I mean, y'all were dating."

"No, no, no. We weren't dating."

And I said, "So he was your chauffeur?"

"Well, I guess he was."

"Well, that's a date."

"No, that wasn't a date. Don't, don't go talking that way."

So I said, "Well, what kept you from marrying him?"

She said, "I loved him to death, but I heard some of the relatives say, 'well, I wonder what the children will look like.'"

And I said, "What the children would look like?"

She said, she said, "Yes. You know, he had a curvature of the spine and we didn't know if it, if it-- children would inherit it."

I said, "That's, that's archaic. You should have talked to a doctor."

"Well, I didn't know what to do, but I worried and worried that I couldn't marry him because I didn't wanna bring in children that were not right."

Isn't that amazing?

Lee Camp

That [00:31:00] is, yeah.

Charlie Strobel

Lee Camp

Huh.

We're going to take a short break, but coming right up, Charlie tells the harrowing story of his mother's murder and the subsequent decision to forgive her killer, defying a prosecutor's call for capital punishment.

What was your relationship like with your mother?

Charlie Strobel

Oh, like every boy's relationship with his mother.

[Lee laughs]

"I don't wanna do it."

"Get up and do it. You're piled in the bed all day long. Get up."

And... wonderful. You know, when I first started going to counseling for depression, people that I know thought that it would've been [00:32:00] because of her death, and it wasn't.

It was really, I went to first, I think, deal with my father.

Lee Camp

Charlie Strobel

And, uh, I knew I would talk about it, her situation, but I dealt with that with the community first, and I think that helped me not to, not to make her death the um, the most, um, compelling issue for me to face. I had already, um, faced it a year or two before she was actually killed.

And, um, nobody really knows this, but I, I guess, I don't know if I should say it, but, uh, well... it was my niece's birthday [00:33:00] and, um, my sister had ice cream and cake ready for us to come by, and I was in the rectory at Holy Name. Had just finished celebrating the Eucharist on a Wednesday night, and, um, I went inside and the phone was ringing.

And uh, my sister, Veronica, she said, "Charles, have you seen Mama?" And I said, "No, why?"

She said, "Well, we've looked all day for her and we can't find her. She's missing. And she would never miss this ice cream and cake, and we don't know what, where she is."

So I immediately had this, just a sense of fright and panic.

And so I went, jumped in the car, and drove over toward her, to her house and, uh, started driving around. The house was not broken into and we [00:34:00] had a key, and we got in and nothing was out of place. So I started this journey, riding around the city, going to places like the funeral homes, I mean like the cemetery, where she might've gone.

And it was in July, and the, um, temperature was f-- you know, 90 degrees. So I was thinking she probably had a heart attack and on the side of the road. So we'd kept going around and around and around. And, um, finally I called back to Veronica's house, Tom and Veronica, and, uh, asked, you know, where, how to stand. "Has anybody seen her?"

And they said, "Well, she's here." I. And I, they said, "Come on."

And so I got in the car and went to their house and there she was. And of course, I, I was just overjoyed just to see her. And her [00:35:00] answer was that her, a girlfriend had reservations for a plane to take her grandchildren who were visiting back to California.

And she got-- Mama, who was named Mary Catherine, she'd say, "Mary Catherine, take me." And wherever Helen wanted to go, Mama would take her.

And she said, "Well, I've gotta call Veronica and tell her I'll be late."

And, and at that time there were no cell phones. It was just the payphones. And she said, "We'll pay, we can call from the airport when we get there."

But when they got there, they didn't do it. And so she was with Helen all that time, and Helen brought her home and that was the end of it.

Well, what nobody knows, or a lot of people don't know, is that when I was walking or, or driving around, finding every reason to [00:36:00] believe that she was run into some bad trouble, I began to think about her dying, and I'm thinking, her death will be a violent death.

And I started to imagine what would then need to be our response. We'd have to say something to explain or to express our, our feelings. So I worked through an entire funeral. I was, I said Father Dan would be the one to preach the funeral. I had her buried. Dead and buried. And so I was overjoyed when I saw her.

So that passes, and several years later, on December the 9th, I'm finishing saying Mass at Holy Name about 5:30. I go into the rectory, the phone rings, it's [00:37:00] Veronica, and she says, "Charles, have you seen Mama?"

And I said no. She said, "Well, we can't find her anywhere."

And at that time I knew, I sensed that this was the real deal. That she was being the victim of, of some violent death.

So I went and did the whole thing. We called people together to try to find her. Officer Bill Hamlin, my brother and I, and Tom, we drove around and around downtown Nashville, and I found her car at the-- parked across the street from the Greyhound bus station in the Union Mission parking lot, and I could tell it was her car.

And I knew it was, because it, because I just knew the car.

The police came and they opened the trunk and found her there.[00:38:00]

I had in my own mind a kind of a dress rehearsal, and I knew exactly what I was gonna say and who, uh, would be participating in the service, and all of the, the surrounding ritual.

So, um, what we said is that we, um, believed in the power of forgiveness, the miracle of forgiveness, and we said we extend our arms in that embrace. And that wasn't something that I just thought of. It was something that I had thought of for the longest time, even back in the days when I was in the seminary. In one moral theology class, we, we [00:39:00] discussed all the major issues - racism, hunger, poverty, homelessness, euthanasia, abortion, and, and capital punishment was one of those.

And we would, we divided the class up into two sides, and one side argued for capital punishment. The other one argued against it. So inevitably when you, we argued, um, against it, the-- inevitably the question was raised, 'well, what would you do if it happened to a member of your own family? And, um, I, uh, I said to myself, 'if I'm against it now in the objectivity of this classroom, uh, I would hope that I would be against it even if it happened to a member of my own family.'

Never, in my wildest imagination, would I have thought that that would be a choice I would have to make. But [00:40:00] in December 9th of 1985, we had to face that choice as a family. And, um, we expressed our opposition and had to go through the court to make sure that it wasn't gonna be changed, that they would not seek the death penalty.

Uh, they, they intended to. And the district attorney came to report, this is what's going to happen. He'll be brought to trial when he was found.

And, uh, I said, "Well, We are on the opposite side of that. We don't want you to seek the death penalty." And they said, okay, and kept going. And I realized they didn't listen.

I said, "Uh, excuse me. I don't think you heard what I said." And I said, "We don't want to pursue the death penalty." [00:41:00]

And they said, "Okay. Okay. We heard that."

Now what-- that cause was some confusion, 'cause I heard it from the public defender's side. They didn't want us to be sitting in the courtroom with the killer.

It's on his side. And so they didn't seek the death penalty. He got three consecutive life sentences, uh, but he was not put to death and he died of natural causes.

I, I did have a interesting reaction when I heard the news that he died. I didn't, I wasn't angry, and, and it wasn't, uh, in my heart saying, 'there, finally, justice is done.'

Probably the closest I could come to identifying how did I react when it, was sadness. 'Cause it, he actually ruined so much of our [00:42:00] life and in, in his own family too. So it was, I was, I was sad to hear it.

Then I, I also came to understand the miracle of forgiveness, which was what, how we phrased it.

My, uh, brother-in-law, Tom, about six months after she died, he said, "Charles, how are you feeling?"

And I said, "I'm, I'm all right. I'm trying to deal with it like you are."

He said, "But you know, there's something about it that, uh, it gives, gives me peace. And I began to talk with him about that.

I said, the, the reason it's a miracle, I, I, I come to believe, is for three reasons. First, forgiveness creates a peaceful heart. While you're [00:43:00] trying to re get revenge, you have-- this person lives inside of you. That is not something that you can deal with without forgiveness. Forgiveness kind of cleanses you and your, your heart. Secondly, it's a miracle in that it gives you freedom that you no longer are stuck in the moment of death. And the, the debate and, and all the stuff surrounding that death.

But you, it's the hard-- and it's the hardest thing that four of us ever had to do. But to do that, to, to, to forgive, allows you the freedom to, um, get on with your life, as hard as it is. And, and then the third [00:44:00] miracle is that it restores a sense of justice, because we believe God is the author of life and death.

It's in the hands of God, whether or not a person lives or dies. And a per-- the person who killed our mother is uh, somebody who has claimed the power to kill that's reserved to God alone. And so, forgiving that person, in my mind is, is a, in a sense, is a way to restore this order of justice.

Lee Camp

Charlie Strobel

Anyway, now how did we get to that?

Lee Camp

Well, Nashville has been [00:45:00] blessed by you and your loving and showing up. And I think back to conversations we've had over the years, and I carry around with me bits of wisdom from you. And, um, I've always felt loved in your presence and I love you and I'm thankful for you.

Charlie Strobel

Oh, thank you. The, that means so much. Thank you very much.

Lee Camp

Thank you.

We've been talking to Charles Strobel, a beloved Nashvillian and founder of Room In The Inn, recognized as Tennessean of the Year several times by lots of folks, but [00:46:00] more than that, uh, a friend to many of us, that we're thankful for.

Thanks for your time today.

Charlie Strobel

Thank you.

Wow.

Did, did, did, did the heart continue to beat? It's like open heart surgery.

This is, I, I feel like this is an operating table. And I should've said that. I guess I have. And I am.

Lee Camp

You've been listening to No [00:47:00] Small Endeavor, and our interview with the recently passed Charles Strobel, a dear friend to many, and a good and faithful servant of his community. We're grateful for his life and work and will miss him terribly.

We gratefully acknowledge the support of Lilly Endowment Incorporated, a private philanthropic foundation supporting the causes of community development, education, and religion, and the support of the John Templeton Foundation, whose vision is to become a global catalyst for discoveries that contribute to human flourishing.

Thanks to all the stellar team that makes this show possible. Christie Bragg, Jakob Lewis, Sophie Byard, Tom Anderson, Kate Hays, Mary Eveleen Brown, Cariad Harmon, Jason Sheesley, Ellis Osburn, and Tim Lauer.

Thanks for listening and let's [00:48:00] keep exploring what it means to live a good life, together. No Small Endeavor is a production of PRX, Tokens Media, LLC, and Great Feeling Studios.